I wanted to reflect on what I felt worked well, what needed improvement, and what future next steps may hold. (I will just focus on the Authority unit in this post, because the Kindergarten inquiry, although similar, took different forms.)One of the most important things you can teach your kids is when and how to say no to authority figures. pic.twitter.com/lM8nn56b92— erinSCIF for America (@erinscafe) November 30, 2019

It was my hope that after experiencing this unit that students would use critical thinking skills when dealing with the authorities - I don't want students mindlessly following orders "just because". At the same time, I don't want students to constantly object to or battle every order, decision or request related to them. It was also challenging to find a way to bring closure to this unit in a satisfying way, but this was resolved thanks to a casual conversation with Matthew Webbe.

Overview

The authority unit branched out of our start-of-the-year examination of authors. (Who is an author? Who can be an author? Who do we expect are authors? How do authors AND readers have power?) We learned and memorized a definition of authority so that we would all have a similar understanding of the basic concepts. ("Authority is the power or the right to give orders, make decisions, or enforce obedience.") Students also learned some sociology via Max Weber's ideas around types of authority. We brainstormed examples of these types - legal, traditional, and charismatic authority. We read books that contained the message that listening to the authorities is a good thing, and we read books that suggested listening to the authorities isn't a good thing. We also read books where legal and traditional authorities differed.

Students drew pictures that had this success criteria:

- included a minimum of 3 people

- provided detail to the characters (no stick people)

- provided detail to the setting (needs a background)

- demonstrated that someone had authority (without using a label saying "he/she's the boss")

We talked about the overt and implied messages that signal that someone has authority. We addressed gender assumptions related to authority. Mid-way through the unit, we had a short quiz to check for understanding on the definition of authority and the two anchor texts we used.

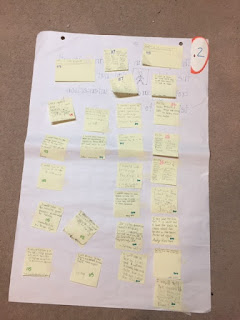

We examined some scenarios in which different authorities clashed, and considered what we would do. Students wrote their thoughts on Post-It Notes.

We watched a short video of a girl who defied her parents, family and village on the issue of child marriage.

This is the incredible story of Payal Jangid, child rights activist and Changemaker award winner. She fearlessly fights against child marriage and has made an amazing impact in her community. You're never too young to change the 🌎🙌 pic.twitter.com/dIf4lpWITH— The Global Goals (@TheGlobalGoals) November 22, 2019

We read the tweet about the Grade 5 students in Utah who left class and sought out the principal when a supply teacher was ridiculing a boy for being thankful about being adopted by two dads.

@AgnesMacphailPS students will be talking about this - when/how/why do you stand up to authority (timing is quite ironic considering the recent OCT publication) https://t.co/tHO9UZQ2ZW— Diana Maliszewski (@MzMollyTL) December 2, 2019

One of the strategies we discovered for pushing against decisions made by authorities was to involve someone with more authority, power and privilege. We discussed the school hierarchy (i.e. who is the biggest authority?), created some scenarios and asked if (and/or when) the principal should be involved. We did some shared writing and created some homework questions for the principal to answer, so we could compare what the students thought was a serious issue and see if the administration agreed or disagreed.

The final task is/was to look at the Parent Concern Protocol poster that sits on our office wall. It describes the steps that parents should take when they disagree with how the school authorities handle a situation. Our classes are in the process of making their own posters in Canva with a "Student Concern Protocol", outlining the steps they should take when they disagree with an authority.

Success

Success

The great thing about teaching lessons to multiple classes is that you have the chance to change things when they falter. Such was the case with the chart paper scenarios. When I first glanced at the answers written on the Post-It Notes, they weren't that thoughtful. The discussion I had hoped would happen as students gathered around the papers with sticky-notes didn't materialize; students were busy writing their own ideas down. For the younger classes, who would already find that task difficult because their writing fluency is still developing, we used the Tribes strategy "4 Corners". Students were read the chart paper and asked to move themselves to the corner they agreed with (i.e. with scenario 6, would you obey the teacher or the parent?) and using that method, greater discussion evolved.

Having a memorized definition was very useful. Students felt confident in talking about authority because they knew what authority was and we all had the same criteria.

The "give homework to your principal" task started out sluggishly until I hit upon inviting students to talk about a time where they themselves were not sure whether or not to involve the principal in a problem. Once they were "allowed" to make it personal, the examples started flowing.

I thought the test and the drawing assignments were going to be too hard for the youngest students and too easy for the older students. Using the same task for 6-year-olds all the way up to 12-year-olds? How realistic is that? Despite my hesitations, they were legitimate assessment methods for a wide variety of ages. Neither the test nor the drawing were "a walk in the park" for the older students. Grade 1s were able to complete the test with support and many did well. If I get permission from some of the students, I will post some of their illustrations.

Room for Improvement

The chart paper scenarios started out as an area for improvement, but with an alteration turned into a success.

I wish we had more time to read more children's literature to and with the students. My original plan was to have students choose a book and then write a short summary of the plot as well as an analysis of whether the message was to obey or defy authority. My students aren't keen writers and the project would have taken too long, but I am sad that they only got to hear those three picture books.

The video we showed of the young girl got some of my students a bit side-tracked. Because the video had English subtitles, I had to read to them because they couldn't read fast enough to understand. This was a barrier. Then, some students overgeneralized and thought Indian girls should always disobey their parents. I had hoped that "I listen to my parents because they are my parents" argument would be called into question with the video, but it wasn't immediately because the students had problems relating to the girl in the video. I worried it was a mistake to show it, until a wonderful girl in Grade 5 said that in her home country, she knew a girl who was 14 years old and married with a child. It was relevant; I just needed to help the students make the connections (and show more images of children from around the world more often).

The poster-making project is difficult to do as a whole class. We started it as a whole class, with choosing the template on Canva to use, but then interest waned. So, I called small groups of students to come and contribute, while the others played, borrowed books, or used loose parts. Some students were more eager than others to work on it. I am also not sure how I can evaluate this poster project because of the support I provided and the different levels of participation.

Future Next Steps

I know that we will continue to refer back to the lessons we learned in this study of authority. We'll be connecting our next unit - furniture - to this one by examining how furniture can communicate the message that the user has authority. Then we'll consider other messages that can be shared via furniture (like comfort, friendliness, wisdom, safety, home, etc) and expand our furniture vocabulary. I also hope that the students will learn how to stand up for themselves and others when authorities act in an unjust manner. I never want them to feel like "you can never say no to a teacher". Yet, I never want them to disrespect authority without just cause. I think they will remember something. After all, when it was announced that our superintendent would be visiting, our students realized and recognized that she is someone who has even more authority than our principal. They get it!

Having a memorized definition was very useful. Students felt confident in talking about authority because they knew what authority was and we all had the same criteria.

The "give homework to your principal" task started out sluggishly until I hit upon inviting students to talk about a time where they themselves were not sure whether or not to involve the principal in a problem. Once they were "allowed" to make it personal, the examples started flowing.

I thought the test and the drawing assignments were going to be too hard for the youngest students and too easy for the older students. Using the same task for 6-year-olds all the way up to 12-year-olds? How realistic is that? Despite my hesitations, they were legitimate assessment methods for a wide variety of ages. Neither the test nor the drawing were "a walk in the park" for the older students. Grade 1s were able to complete the test with support and many did well. If I get permission from some of the students, I will post some of their illustrations.

Room for Improvement

The chart paper scenarios started out as an area for improvement, but with an alteration turned into a success.

I wish we had more time to read more children's literature to and with the students. My original plan was to have students choose a book and then write a short summary of the plot as well as an analysis of whether the message was to obey or defy authority. My students aren't keen writers and the project would have taken too long, but I am sad that they only got to hear those three picture books.

The video we showed of the young girl got some of my students a bit side-tracked. Because the video had English subtitles, I had to read to them because they couldn't read fast enough to understand. This was a barrier. Then, some students overgeneralized and thought Indian girls should always disobey their parents. I had hoped that "I listen to my parents because they are my parents" argument would be called into question with the video, but it wasn't immediately because the students had problems relating to the girl in the video. I worried it was a mistake to show it, until a wonderful girl in Grade 5 said that in her home country, she knew a girl who was 14 years old and married with a child. It was relevant; I just needed to help the students make the connections (and show more images of children from around the world more often).

The poster-making project is difficult to do as a whole class. We started it as a whole class, with choosing the template on Canva to use, but then interest waned. So, I called small groups of students to come and contribute, while the others played, borrowed books, or used loose parts. Some students were more eager than others to work on it. I am also not sure how I can evaluate this poster project because of the support I provided and the different levels of participation.

Future Next Steps

I know that we will continue to refer back to the lessons we learned in this study of authority. We'll be connecting our next unit - furniture - to this one by examining how furniture can communicate the message that the user has authority. Then we'll consider other messages that can be shared via furniture (like comfort, friendliness, wisdom, safety, home, etc) and expand our furniture vocabulary. I also hope that the students will learn how to stand up for themselves and others when authorities act in an unjust manner. I never want them to feel like "you can never say no to a teacher". Yet, I never want them to disrespect authority without just cause. I think they will remember something. After all, when it was announced that our superintendent would be visiting, our students realized and recognized that she is someone who has even more authority than our principal. They get it!

You're amazing. I struggle wth this dichotomy all the time, particularly teaching intermediate. How do I encourage my students to question authority when they feel it's necessary, while also asking them to respect authority when it's warranted? We're also having these conversations at home, as Mr 16 struggles with things being presented in class as binary, and that sometimes causes him to ask questions which are seen as questioning the authority of the teacher. Sigh. It's never an easy line to walk, but we ask our students to do it all the time.....

ReplyDeleteLisa, this is exactly what I struggled with too. It was interesting to see how, when I told them about the TDSB dress code and said it was true/real, how many of them put on their hoodies. And then I have my brilliant special education teacher who admitted that she is still particular in her class - because she has students who don't understand the societal ramifications when a lot of skin is shown. I've heard it said by quite a few educators "you can't say no to a teacher" and that's not true (I try to modify it by saying "if what a teacher is asking you to do is reasonable, then you shouldn't say no") but giving that freedom of expression does sometimes lead to less respect being given to me compared to a "do as I say and don't question me" type of teacher. I really feel for your Mr. 16 because the teachers can be all in favour of questioning authority - unless it's their authority in question! Ergo the unit and the conversations, which I hope will continue.

ReplyDelete